Ownership Is Where Many Engineering Careers Stall

Why “doing your part” isn’t enough to reach senior level

“I did what I was asked.”

That sentence explains more stalled engineering careers than any technical skill gap.

Most mid-level engineers are reliable. They ship work. They follow process. They escalate risks. But they are still not quite senior yet.

The issue is usually ownership.

In this article, I’ll walk through how ownership evolves from junior to senior engineers, and what ownership looks like in practice.

Ownership Skill in a Nutshell

Junior Engineers: Task Ownership

At the junior level, ownership is mostly about executing assigned work correctly.

Work starts with a clearly defined ticket. Requirements and steps are usually spelled out. Decisions are made by someone else.

If something is not clear, they push back and they expect others to resolve the ambiguity.

Success is simple and concrete:

My responsibility ends when the task is done.

At this stage, junior engineers are building fundamentals: learning the codebase & understanding team norms. The scope of ownership is intentionally narrow. They are mainly learning how things work in general.

Mid-Level Engineers: Project Ownership

At mid-level, engineers start owning projects or features.

The difference from pure execution is that they start making decisions. They help stakeholders understand the technical challenges and effort. They help them update requirements to achieve the best outcome.

At this stage, they still need help understanding the big picture from senior developers, but they can make most decisions themselves and deliver end-to-end.

But there’s a common ceiling.

When requirements are unreasonable, priorities conflict, or incidents happen, many mid-level engineers pause. Some can make decisions, but most can’t. They escalate and stop.

At this stage, success usually means:

My responsibility ends when the project is delivered.

Senior Engineers: Outcome Ownership

Senior engineers own outcomes, not just work.

They take responsibility end-to-end.

They act even when no one explicitly asks them to.

They make progress in ambiguity instead of waiting for clarity.

The definition of success changes to be more business-oriented:

My responsibility ends only when the problem is solved.

Senior ownership often looks invisible on paper. It’s hard to track it on the Jira board, such as starting a tech design to align teams and pushing back an unreasonable request.

This is also why senior engineers are trusted with larger scope. Managers don’t need to micromanage them, because they don’t stop at “done” if the outcome is still broken.

Mid-Level Engineers Avoid Ownership Without Realizing It

In my experience, this avoidance usually comes from habit.

They Are Used to Clear Boundaries

Mid-level engineers often grow up in environments where responsibilities are clearly segmented.

PM defines scope.

Senior engineers make the key technical decisions.

Mid-level engineers execute what’s assigned.

That structure works well. But over time, it creates a mental model where stepping outside a defined boundary feels like overstepping.

When something falls between roles, the default response becomes: someone else owns this. That’s how most team work, and that’s how the system has conditioned people to think. It comes as a habit.

They Over-Rely on Senior Engineers

The clear boundaries also create another problem: they stop at escalation.

There are many mid-level engineers not being in the part of the decision-making process.

After they escalate a problem to senior engineers, they wait. They don’t make their own recommendations in front of senior engineers.

In that case, escalation becomes the end of the action, ownership quietly stops there.

For example, a mid-level engineer might identify two possible solutions to a high-latency issue, but not sure which is better. They escalate to senior engineers and wait for their input. The senior makes the decision, and the issue gets fixed.

Nothing is wrong with that, but in this case, the mid-level engineer miss the learning opportunities. They could have proposed a recommendation, explain tradeoffs, and get feedback on their thinking. Many mid-level engineers miss opportunities like this.

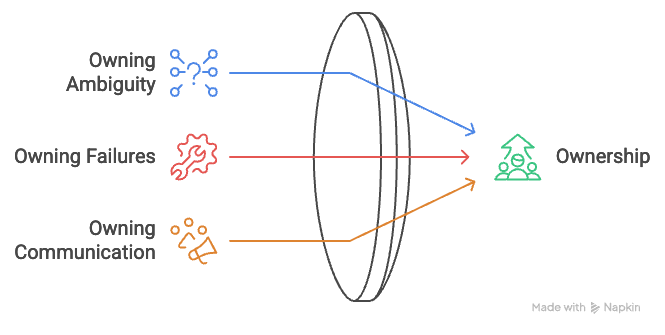

What Ownership Looks Like in Practice

Ownership sounds abstract, but in practice, it’s how you respond when things are unclear or unfinished.

Owning Ambiguity

When facing unclear requirements and conflicting priorities, owners don’t guess blindly and also don’t freeze. They ask clarifying questions, outline options, and move the conversation forward.

Typical behavior looks like:

“Based on what we know, I’d recommend this, unless we discover X.”

“I’ll need to talk to my manager, but I’ll get back to you by the end of tomorrow.”

The key is to move things forward. Even a small move is more useful than no action.

Owning Failures/Incidents

When something breaks, owners don’t stop at fixing the immediate issue. They stay with it end-to-end.

In practice, this looks like:

Clearly stating what went wrong.

Focusing on system causes (and not blaming).

Making sure a prevention plan exists.

Owning failures is about ensuring the same problem doesn’t occur again three months later.

Owning Communication

Owners don’t assume information magically spreads. They close loops, confirm decisions, and make sure stakeholders know the progress and results.

This often looks simple:

Summarizing discussions in writing.

Explicitly calling out owners and timelines.

Checking that everyone shares the same understanding.

None of these actions require a title. They require the mindset that if you care about the outcome, it’s your responsibility to make progress visible and real.

Start Small, Start Today

Practicing the ownership skill starts with small, deliberate shifts in how you approach your work.

If you want to start today, the easiest way to begin is to pick one area and fully own it. One project. One recurring issue. One process that keeps causing friction. Don’t try to fix everything at once.

For example:

Take a problem and turn it into a concrete proposal.

Follow one issue past escalation and stay with it until it’s resolved.

Close one feedback loop that usually gets dropped.

You can also ask your manager for opportunities.

Consistency matters more than scope. Owning something end-to-end once a month is more valuable than half-owning ten things at the same time.

Over time, the scope grows naturally.

Last Words

Ownership is about what you choose to carry when things are unclear, unfinished, or uncomfortable.

Senior engineers are trusted because they don’t stop at “my part” when the outcome is still broken. You already have the skills. You only need that small change of mindset.

That’s it for today.

If this way of thinking resonates, I write about senior-level mindset, ownership, and career growth for engineers every week.

I’ll see you in the next post.

Adler from Tokyo Tech Lead