Stop Negotiating Capacity

Overcommitment is one of the most toxic bad habits a team can pick up. Here's how it happens and a better way forward.

Today’s post is brought to you by Christine Miao , author of Thoughtful Engineering. Take a look at her work if you’re interested :)

Let’s Start

The sprint is done, but the backlog isn’t. After a mad scramble to close things out, “follow-up” tickets are made and stories spill over.

You find the usual suspects at retros. Unplanned work. Scope creep. Low quality estimates.

Everyone agrees it’s not ideal—but hey, that’s just how it goes, right?

And just like that, the team picks up one of the most toxic habits of modern software engineering:

Overcommitment.

Overcommitment erodes productivity in four compounding ways:

Wasteful overhead: Scoping, estimating, and planning for 20 items when your capacity is 10 is inherently wasteful.

Lower agility: as unplanned work comes up, you can’t adapt quickly. If you’re at 80% capacity, adding in one new thing is easy. But at 110%? It’s an entire optimization exercise.

Reduced morale: No matter how hard they work, the team always feels behind. Morale drops and burnout follows.

Lost trust: Consistently missed commitments create the perception of low performance—even for strong, hardworking teams.

Every item over your true capacity will undermine your team’s efficiency, agility, morale, and credibility.

This is the poison of overcommitment. But it happens…all the time - and teams accept it as inevitable and normal.

Even when teams do try and fix this, they often make things worse. Leaders crack the whip on “underperforming” teams. More bureaucracy is put in place to improve estimates. The team makes even bigger promises trying to “make up” for lost ground.

But the real problem hides in plain sight: the sprint planning process itself.

Just a Normal Sprint

Let’s look at a typical sprint:

The product team gathers requirements from all over the org.

They put those requirements into the backlog, in rough priority order.

Engineers scope and translate these stories into story points.

Based these estimates, product and engineering negotiate on a final sprint plan.

…but here’s what’s happening under the surface:

Without considering capacity, the product team constructs net-new, aspirational wishlists every single sprint.

Product has no visibility into what’s hard vs. easy, so they throw items into the backlog “just in case” it’s low-hanging fruit.

Engineers scope and plan much larger backlogs then they could ever conceivably handle.

More time and energy is spent as product and engineering negotiate a final sprint plan. Product naturally pushes for more, and engineering - thanks to human nature - tries to please and oblige.

It ends up serving no one. Engineers face constant upheaval and reprioritization. Product can’t focus on serving customer needs. Stakeholders waste money and time as deadlines are missed.

A Step Back

In any department outside of engineering, this kind of planning would be sheer madness.

Does your finance team open the floor to “feature requests”? Does marketing do public demos to assure everyone else that that work is getting done?

Engineering is the exception here because it lacks something that these other departments often take for granted.

A shared, intuitive sense of capacity.

We can all picture what marketing or ops or finance or sales is doing. We understand the challenges and bottlenecks of those teams. It’s why we don’t interrupt marketing meetings to ask why they’re not running Superbowl ads.

But engineering capacity, and the factors that drive it, are completely invisible outside of engineering. Non-technical stakeholders can’t “see” a monolith. They don’t understand “tech debt” in practical terms. The concept of platform maintenance - aka the very foundation of engineering success - is foreign and invisible.

Instead, they can only rely on blind trust.

And when humans feel in the dark and out of control, anxiety takes the wheel. Through this lens, our sprint processes make a lot more sense - they're not so much mechanisms to help us ensure delivery, but soothe human anxiety.

Building a Shared Understanding of Capacity

The only antidote is to build a true, working understanding of how engineering works. That’s where technical accounting can help - by mapping resourcing, architecture, and maintenance.

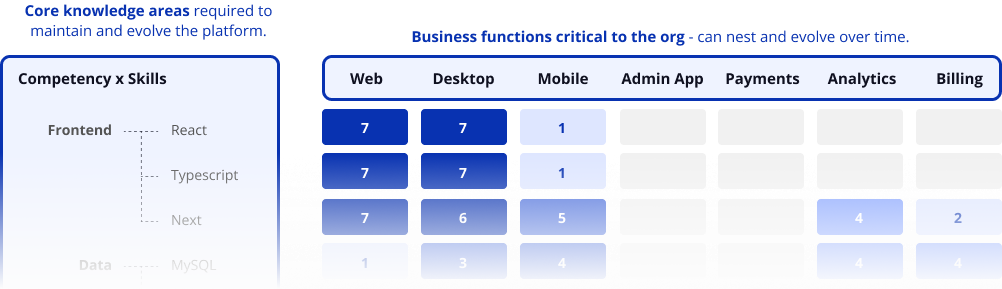

Here’s a typical platform map:

The rows represent different clusters of knowledge required to maintain and evolve the platform. The columns represent core business functions.

The colored intersections represent the number of ICs who can work on any given part of the platform.

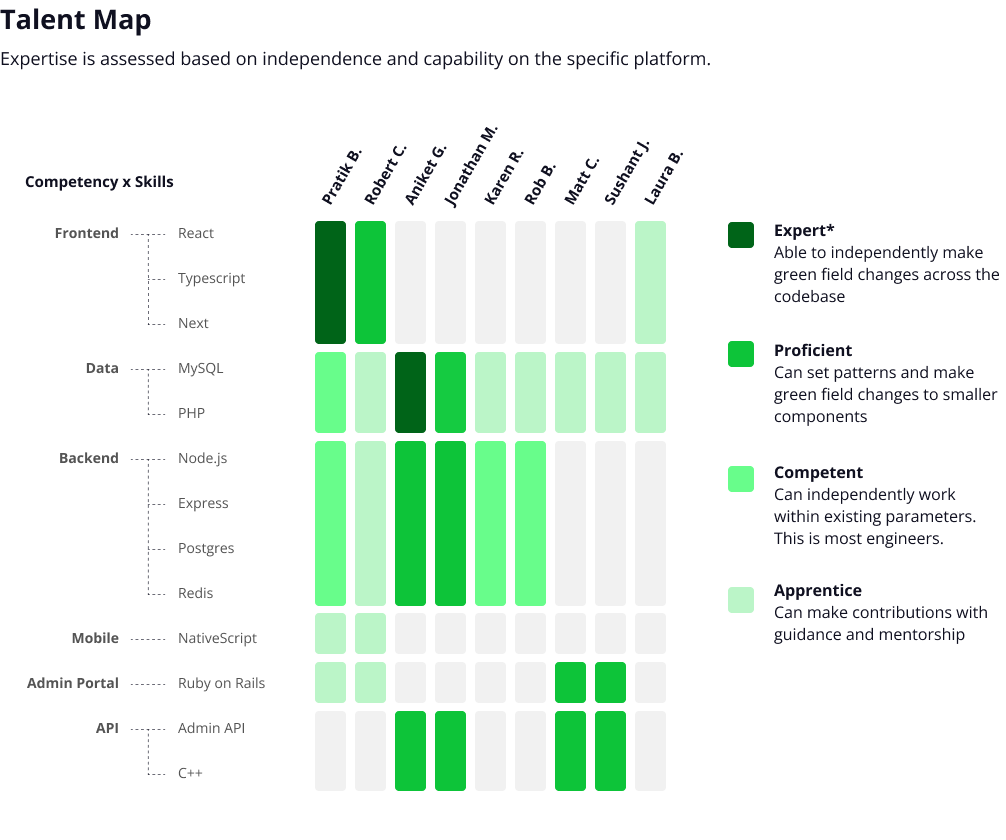

This view is constructed by surveying and understanding the capabilities of the existing team relative to relevant parts of the platform, right now. Ex: we don’t care whether or not someone “is good at frontend” - we care that they know the frontend relative to the platform in question.

In the same way, you can plan projects.

You can compare the diff between skills required to deliver goals against your current actual skills. This view works across a single sprint, or across your quarterly planning.

This is particularly valuable as stakeholders make new requests. If the business asks to swap in “one more small thing”, you can highlight exactly where and why that “small thing” isn’t doable given your current capacity in a way that those stakeholders can easily understand.

It also helps surface hidden costs and unseen bottlenecks. For example, a “front-end project” would typically be simply assigned to a “front-end dev”, but may ultimately require back-end expertise to integrate the work effectively. This kind of planning surfaces that hidden complexity/potential bottlenecks upfront.

When you plan in this way, you not only create a shared baseline of common sense across the organization, you also grow the entire team’s technical fluency

Stakeholders build knowledge every single cycle. They start to understand what’s hard, why some things take longer, and where bottlenecks are.

In other words, they start to understand engineering at a strategic level.

They stop generating bloated backlogs that drain time/morale to manage.

They stop negotiating capacity, trying to squeeze in “just one more thing”.

Instead, they have something infinitely more valuable and elegant: a common-sense, intuitive pulse on their capabilities.

AKA: the foundation of a sustainable, high-performing team.

Last Words

Thank you for reading the post!

❤️ Click the like button if you like this article.

🔁 Share this post to help others find it.

About Tokyo Tech Lead

Tokyo Tech Lead is a blog/newsletter for engineering leaders. Check out this overview guide for all the resources it provides.

Work with Me

📗 Personal Coaching: I provide personal coaching and consulting service. Find details here.

✍️ Guest Post: If you are interested in writing for Tokyo Tech Lead, check this post.

If you want more content like this, consider subscribing to my newsletter.

See you in the next post!